|

Page 1 of 5 Popular music and cinema: how the rock artist is represented on the big screen Alessandro Bratus

Università degli Studi di Pavia This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

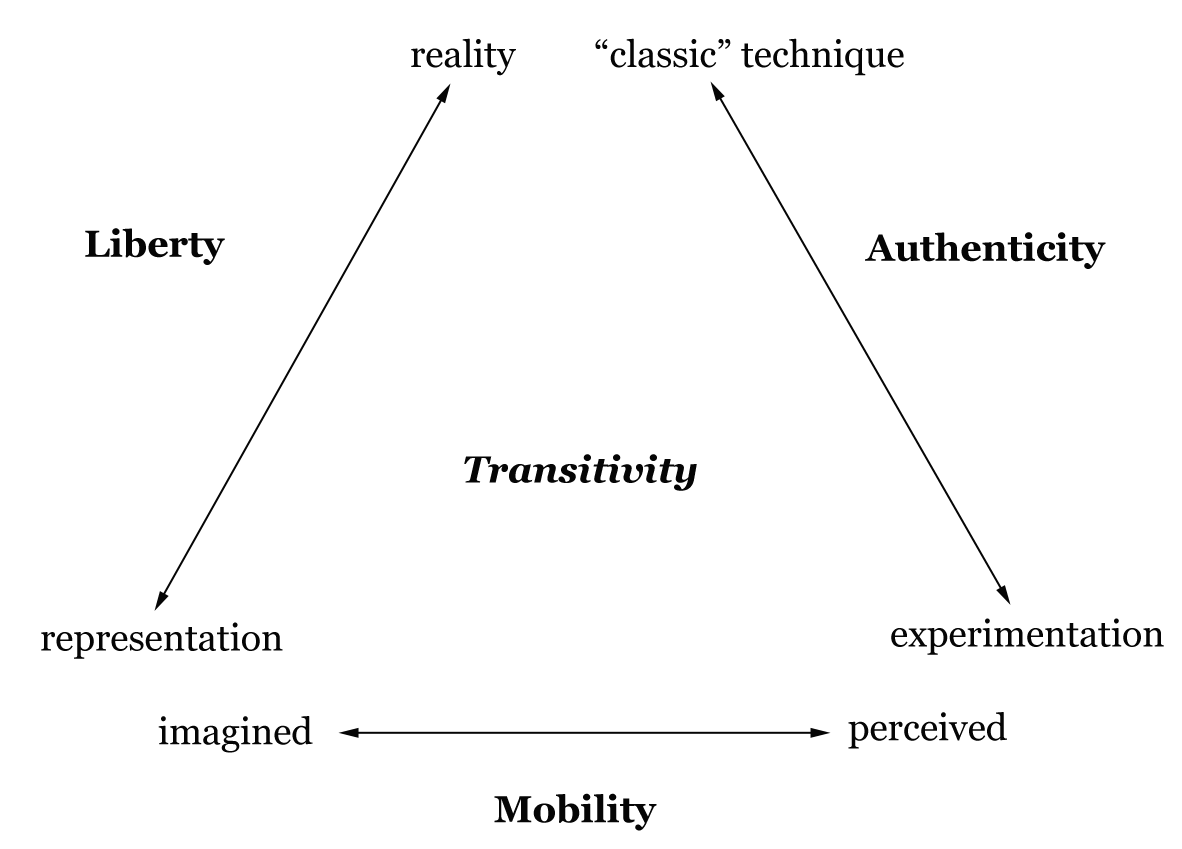

The question of how rock is narrated in cinema raises very interesting issues in the context of the current scientific debate concerning audiovisual communication and the methodologies of its analysis. Gaining an understanding of the configurations taken on by the relationship between form and substance, content and container, can open up useful perspectives in the analysis of a range of materials which have not yet been the subject of a specific enquiry into the structural organization of sound and image. In spite of the heterogeneity of genres and directing techniques, these films do seem to represent a category possessing unitary features; the values they express, as indeed the similar narrative and formal procedures, lay the foundations for a shared language based on recurrent situations and strategies. 1. Reflections on direct cinema as the basis for analysing rock films As Keith Beattie points out in his historical and critical account of documentary film, direct cinema most popular and commercially successfull subgenre is the so-called ‘rockumentary’ (Beattie 2004: 97-102). This kind of films gave the go-ahead for a major development within this cinematic trend, especially bringing in “further revisions to a basic observationalism” (ibid.: 102) and helping in the elaboration of a distinct style for movies connected to the rock world. According to Dave Saunders, the affinity between this approach and the world of popular music is not just an aesthetic question but indicates a fundamental passage in the historical evolution of the technique: this is the very moment when direct cinema acquired an artistic autonomy, distancing itself from the conception of mere reporting (Saunders 2007: 52-3). In the 1960’s, a crucial period for the definition of new meanings in art forms on account of the spread of electronic media, the conjunction of rock music and an innovatory approach to film directing can be interpreted as an attempt to tackle a subject which, for its specific characteristics, could no longer be narrated through the standard means. David Baker (2005) argues that the favoured communication channel is expressed by the sharing of some fundamental ideas (mobility, authenticity, freedom) which can be summed up with reference to the concept of transitivity, as showed in Table 1.

Table 1. Transivity and its values in the context of direct cinema and rock. Referring to these coordinates, we can propose a set of parameters as a more wide-ranging analytical tool to bring, within a single conceptual field, films featuring popular music and its protagonists. In relating these ideas with the typical formal and material techniques of the films analysed (Table 2), we have suggested a relationship between opposite features which shapes a continuum of possibilities with each of the three ideal dimensions proposed by Baker. This gives us a unitary space – defined by transitivity – encompassing the most diverse modalities of the narration of rock on the big screen.

Table 2. Transitivity space, defined both from the point of view of Baker’s values (2005) and directing choices. From the point of view of audiovisual analysis, this theoretical scheme operates at the level of what Nicholas Cook calls “cultural synaesthesias” (1998: 49), where sound and image are “related to one another not directly, but through their common association with transcendent spiritual or emotional value” (ibid.: 55). In other words, the music is treated merely as a repository of values and ideas, leaving untouched the analytical level concerning the strategies for sound organization in relation to the image, and vice versa. The latter feature represents the logical counterpart of the conceptual construct presented in the above table: in this context the stated values denote what Richard Middleton refers to as ‘secondary signification’. On the other hand the structural level of the text is linked to processes of primary signification, in which such ideal constructs interact dialectically with the modalities of presentation of both audio and video (1990: 176-239). In a domain in which the relationships between media dimensions vary according to the object analysed (Borio 2007), rather than conforming to a fixed hierarchy, interpreting them in the light of such a conception and investigating the relationship between formal values and devices may be the key to viewing the plurality of outcomes we encounter in rock films in a common theoretical framework. |